By Rev Christine Hall

Introduction

I spent three months in Canada in the autumn of 2007 and experienced amazing hospitality from many people. The original purpose was to study aboriginal liturgy and spirituality in the Diocese of Rupert’s Land, mainly in the city of Winnipeg Manitoba, but I extended the trip to include a three week placement at Christ Church Cathedral in Vancouver, and I found time to visit Toronto (at the beginning) and Churchill (in the middle).

Aims and Objectives

My main aims and objectives were:

- To investigate the Liturgies of the First Nation Peoples and examine how their spirituality is expressed (or not) in those Liturgies.

- To study the way in which First Nation Peoples are integrated into the wider church environment and experience the church in that environment.

- To broaden my experience of the Anglican Church – to experience a Church which is not the established church and to observe what being a priest in a different setting is like. (Added in the light of the extension to Vancouver)

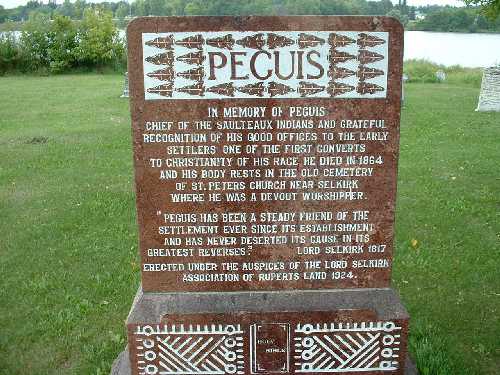

Brief Description of Visit

I started at Toronto for a few days (to visit Niagara Falls!) and then travelled by train to Winnipeg, where I spent nearly two months. In Winnipeg I experienced the Sacred Circle Weekend, the Faith Horizons weekend, the Diocesan and local church interactions with First Nations as well as a 2 week stay on at Peguis. I then travelled to The Pas for a few days at the Henry Budd College, then up to Churchill to see the polar bears. I then came back to Winnipeg for the Manito Ahbee before continuing my journey to Vancouver. I had a 3 week placement at Christ Church Cathedral there.

What I Enjoyed Most

I enjoyed so much of the trip that it’s quite hard to pick out one aspect. Perhaps the Manito Ahbee was the most exciting (3/4 November). This was a festival where the First Nations danced and made music for themselves. As one speaker put it (in a non politically correct form): he hadn’t seen a white man for 3 days! However, I could not have appreciated it so much without the preceding experiences. I caught up with friends that I had made there; I enjoyed them enjoying themselves in their own fashion; I had come to know, at least in part, some of the aboriginal spirituality and hospitality that underpinned their celebrations.

What I Enjoyed Least

I was most frustrated by the experience at The Pas. Here I was promised further interaction with First Nations, which never really transpired. Again I was welcomed and I managed some interaction with the people at the Opaskwayak Reserve, including a service in Cree. However the visits to other nearby Reserves had not been planned and I had to accept very quickly that such visits were unlikely to take place. This was frustrating, and I think mirrored a similar experience of another student from the North Thames MTC last year. However, it was good to visit The Pas and despite that irritation it was good to experience another facet of life in Manitoba.

Major Areas of Learning

Culture

There actually seemed to be three strands of aboriginal culture current in Manitoba:

- The original traditional culture;

- The Anglican Prayer Book / Country and Western singing culture that I experienced on the reserves and in Winnipeg;

- The indigenous culture taught in schools – ‘official’ aboriginal culture based on an assumed conglomeration of ideas, often originating in Western Canada, where the aboriginal peoples had retained their culture for a longer period.

I experienced some of the original culture on the Peguis Reserve, for example when we went to collect and dig up roots for medicine. The overwhelming hospitality I received there was also part of that. I also observed the closeness of family, and a spirituality concerned with the wholeness of the human being. The idea of talking in a circle and listening to each other rather than our adversarial European method of justice or reacting to each other means that reconciliation might take longer but actually be more permanent. The assumption in the past would have been that the Band would need to find a community way forward out of difficulty and wrong doing. That notion of restorative justice felt very attractive. I experienced a similar circle at one hospital and it was very moving to listen to what was on people’s hearts. We passed a talking stone around and spoke. In England we interact in a much more confrontational manner and there is always the temptation when hearing such stories to offer advice, to make it better, or to trump the story with something bigger. There you were expected to honour the time with what was on your heart; it might partly be a response, but it also had to be something equally deep and meant that you needed to respect each other – patients and staff suddenly became much more equal, even though there were obvious boundaries which needed to be kept.

Theological Understanding

My interest was liturgical and spiritual, so the experience of First Nation Liturgies at the Jessie Saulteaux Centre was fascinating. It was the weekend of the autumn equinox and the Ceremonies were effectively a retreat and an opportunity for us to purify ourselves, to be healed and to give thanks to the Great Spirit or Creator. There was hospitality, and God might take whatever shape we wanted – whether God be the overtly Christian God or not. It was perhaps reminiscent of the way Paul described the unknown god (Acts 17.23).

There was a Sweat on the Thursday evening when we arrived – a chance to rid ourselves of all the uncleanness of our physical selves as well as our emotional and spiritual selves. We prayed in that small space, or sauna, very aware of each other’s bodies in a way that would be unheard of in an English retreat. It was like being in the womb of the earth, and we were being re-created; healed and ready for what life might throw at us next. The rocks (grandfathers and grandmothers) brought in gave us a thread of history and timelessness; prayers to the four directions gave us a chance to pray for young and old, and all peoples. It was an opportunity to experience the enormity and graciousness of God.

After this ceremony, the Sacred Fire was taken to a tipi and then guarded day and night by each of us taking turns. This gave us a chance to hear stories, to take time on our own, as well as to listen and be with God.

I do not want to impose a Christian interpretation, because that takes away something of the authenticity and validity of the occasion, but spiritually and in terms of a rite the next two days felt very reminiscent of Holy Saturday. On the Sunday, we were up before dawn (which helped the analogy) for a further ceremony. We gave thanks for the gift of life, for being created, for love, for humility, for courage and healing and for respect. It certainly gave material for an Easter sermon albeit unusual.

During this weekend and on a number of other occasions I experienced the cleansing of a smudging ceremony. I put one into the liturgy I assembled for the Sacred Circle Weekend that took place whilst I was in Winnipeg. This was a cleansing action and in that liturgy took the place of the prayers of preparation. The smudge was also used in a similar way at the beginning of the Eucharist on one Sunday at St Matthew’s in Winnipeg. I can understand some people’s aversion to mixing ‘pagan’ ceremonies with Christian ones, but in this context it seemed highly appropriate. It is something that has been done throughout Christian history. Here it was a way of affirming and respecting the aboriginal spirituality that we have done so much to rubbish and remove. It was led by Christian aboriginal people, and thus the possibility that it was another example of taking over something that we cannot perhaps completely understand was minimised.

Application of Learning

This report cannot do justice to the range of experiences and the hospitality that I experienced in Canada. The spirituality and hospitality of the First Nations is something that affirmed the way I try to interact with the stranger I meet in the hospital bed especially when I offer chaplaincy to those of other faiths or denominations. The different liturgies (both aboriginal and Anglican) will stimulate ideas for the future, especially quiet days, retreats and times which call for something out of the ordinary. The experience of different cultures (again both aboriginal and Anglican) and to see international arguments (particularly in Vancouver) from a different perspective has broadened my views and hopefully will enable me to continue to appreciate and love people who start in a place very different from me in my ministry.

Questions and Issues for the Future

The main issues that I want to keep thinking about are:

- The aboriginal way of consensus action rather than our adversarial one. It is a way of being that inevitably takes much longer to resolve an issue, but may in the end make such a resolution more acceptable to all those involved. I can see that in our society it might be difficult to use on occasions. I would also like to learn more about Restorative Justice for similar reasons.

- The international church – a church that was not an established church. It was also, fascinating to experience the Cathedral in Vancouver and be part of a community that had agreed Same Sex Blessings. As a consequence it felt like a much more open community: ready to welcome all people as flawed human beings. They had moved beyond the secrecy of some people trying to hide part of who they are, and other people making sure they didn’t ask. It was a community that accepted and bestowed God’s love to all. This contrasted with a much slower movement on these issues from the Diocese of Rupert’s Land which was clearly the right action for them. Both Dioceses struggle to find the way forward for them in their context, but holding and noticing the pain of others mirrors Anglicans all over the world.

Other Information/Support

I think part of the delight and learning was to forge a way through the possibilities that were available. I had a wonderful time and it will continue to inspire and influence me in ways that I probably cannot imagine during my future ministry. It has played a significant part in my formation and so my thanks to the Trustees and all those who I met. I’ve also been staggered at how much friends, family and colleagues have enjoyed the bulletins that I sent home whilst I was away. It has been an experience that has actually influenced many people and as such is an example of God’s grace and creative love.