By Simon Kirby

My family and I had the privilege of spending an extended period living on the Peguis Reserve in Manitoba in the autumn of 2002. As well as reading about historical accounts of missionary practice, I spent time talking to people on the reserve about their own experiences. My examination of historical sources and conversations with individuals showed that the problem for many missionaries in history was that they had limited the gospel to theological and moral concerns, and those concerns were expressed through their own cultural understanding of the gospel and of the people to whom they ministered. DJ Bosch writes:

“The West has often domesticated the gospel in its own culture while making it unnecessarily foreign to every culture. It will always be a sign of contradiction. But when it is in conflict with a particular culture, for instance of the Third World, it is important to establish whether the tension stems from the gospel itself or from the circumstance that the gospel has been too closely associated with the culture through which the missionary message was mediated at this point in time.”

(D J Bosch, Transforming Mission, Orbis, 1991, p 455)

The gospel is about good news that leads to the transformation of individual lives and communities. However the challenge for the person taking that good news to those communities is whether they can present the gospel without presenting their own cultural expectations. The history of the people of Peguis illustrates why that challenge is so difficult.

In rehearsing the historical legacy of the early (and not so early!) missionaries, Bosch points out that:

“The Problem was that the advocates of mission were blind to their own ethnocentrism. They confused middle-class ideals and values with the tenets of Christianity. Their views about morality, respectability, order, efficiency, individualism, professionalism, work and technological progress … were without compunction exported to the ends of the earth. They were therefore predisposed not to appreciate the cultures of the people to whom they went – the unity of living and learning; the interdependence between individual, community, culture and industry; the profundity of folk wisdom; the proprieties of traditional societies – all these were swept aside by a mentality shaped by the Enlightenment which tended to turn people into objects, reshaping the entire world into the image of the West, separating humans from nature and from one another, and ‘developing’ them according to Western standards and suppositions.”

(Transforming Mission, p 294)

This is not to deny that the missionaries did some good work. Many indigenous people are grateful for the contribution that the early missionaries made in areas such as education and farming. Where missionaries took time to listen to the native people they discovered many things in both cultural behaviour and religious belief that could be affirmed when translating the Gospel. A striking example is the native understanding of the involvement of Creator God in the world containing similarities to the Old Testament creation narrative, such that Charleston is able to write:

“Native people also have an ‘Old Testament.’ They have their own original covenant relationship with the Creator and their own original understanding of God prior to the birth of Christ. It is a Tradition that has evolved over centuries. It tells of the active, living, revealing presence of God in relation to Native people through generations of Native life and experience. It asserts that God was not an absentee landlord for North America. God was here, on this continent among his people, in covenant, in relation, in life. Like Israel itself, Native America proclaims that God is a God of all times and of all places and of all peoples. Consequently, the ‘old’ testament of Native America becomes tremendously important. It is the living memory, the living tradition of a people’s special encounter with the Creator of life.”

(‘The Old Testament of Native America’ in J. Treat, Native and Christian, p 73)

My time on the Peguis Reserve and in Winnipeg was incredibly valuable in that it allowed me to engage with issues of inculturation and acculturation, at a very personal level. Through many conversations and observations I believe that I began to learn more about the Gospel and the challenge of communicating to different cultures without imposing one’s cultural baggage.

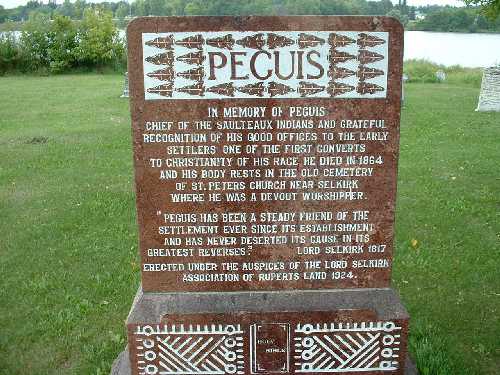

History generally does not paint a very good picture of the involvement of the Church among the native people in Canada. St Peter’s Church in Selkirk, MB, for example, was built on fertile land originally ceded to the Cree people, but then re-allocated to European settlers when the Cree were forcibly re-settled on the much less fertile land of the Peguis Reserve many miles to the north. I hope that what I have learnt from the past will enable me to minister in the future with a greater awareness of the cultures to which I minister, and how to communicate the Gospel to them graciously.